Intro to the origins of Patek Philippe’s wonderful Minute-Repeater aura

Hello everyone,

I thought I should have a look at why Patek Philippe’s reputation in Minute-Repeater history is at such high level today. I’ve been taking my time, like most of us, discovering, exploring the world of watches in general, and of Patek Philippe in particular. I knew a few about their mastery for this very special complication and what the brand represents in the Minute-Repeaters’ rebirth and evolution. However, I left it aside for later down the road. I enjoyed a few of the videos that can be found whether on Patek’s website, YouTube etc…, but I knew it would take time to go deeper in their history.

Aside from some alternative readings, I decided to start a very enjoyable journey with the help of Patek’s Minute-Repeaters book.

From past to present

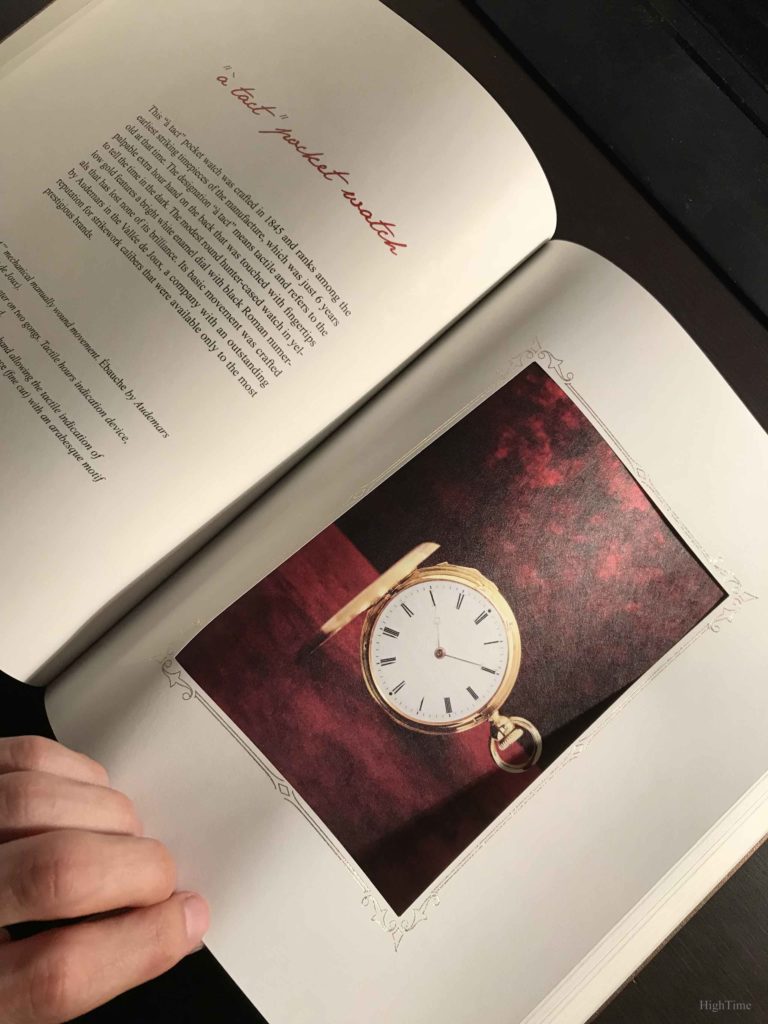

Not long after Antoine Norbert de Patek and François Czapek opened their Geneva workshop in 1839, they unveiled their first Repeater watches. It started with a Quarter-Repeater-only this same year (rings at each 15 min.) and ended with a Minute-Repeater in 1845 (after releasing crescendo 3 intermediary levels of repeaters meanwhile).

When in 1851 Patek Philippe & Co was created from the new partnership with Jean-Adrien Philippe, the Minute-Repeaters were something the brand was already known to master. This same year, first Patek pocket watch with Grande Sonnerie.

The first mechanisms displaying an acoustic signal on demand dated from the end of the 17th century (clocks etc…). From that time Patek has been developing those miniaturized mechanisms.

For the anecdote, there was a pause after the WWII as, in the 1960s, there was no demand for such complications anymore. It’s only in the context of its 150th anniversary celebrations (1989) that Patek Philippe decided to craft Minute-Repeaters again. I could then realize how important this decision was and be thankful for bringing them back for our pleasure and for traditional watchmaking as a whole.

The recent wide Patek Minute-Repeater collections weren’t built in one day and they are the result of a very long expertise development over the decades, and mainly visible through:

- The setting and sound quality (rhythm, tone, harmony…);

- The way the ringing mechanism is combined with other significant complications;

- Usually rather limited sizes compared to what these cases contain.

I think this is part of the brand’s know-how and a part of why its reputation is such today.

Once upon a time…

Let’s go a little further back when Daniel Quare was claimed in 1686 by the King of England as the legitimate inventor of the first repeater mechanism. It’s only during the century to follow that French and English (and in a lesser extent Swiss) watchmakers “competed” to find new solutions to make it convenient (starting with a chain before using a flank slide etc…).

In the end of the 18th century, Abraham-Louis Breguet invented the ring gongs to replace the iron bell that was used.

The final stage of repeaters, the Minute-Repeater, was finally developed late of the 18th century. It was firstly attributed to Thomas Mudge in 1750 for a while but it seems that some were found 30 years earlier in Germany. I guess it will be tough to find who was first as the watches weren’t always signed and that many archives have been lost since.

Some of the timepieces, prior to the creation of Patek Philippe, can be seen in the Patek Philippe Museum, showing their respect for such history. By the way, this underlines the importance of creating such Museums, in order to preserve this horological heritage (and not only the brand’s pieces). The older pieces aren’t often the ones that clients are interested in and I think this shows the appreciation the Stern family has for this legacy.

After 1845, the first pocket watch with “Grande” and “Petite” Sonneries was crafted for a cardinal in Italy. In the next 60 years, many Minute-Repeater pocket watches with additional complications (PC, Chronograph, Equation of Time etc…) were produced. The Westminster chime available for these watches had 5 gongs and 5 hammers.

In 1853, we see the first Patek pocket watches with Minute-Repeaters.

I think it is also important to emphasize that for all these years, the brand has proven to master the miniaturization of such complex movements. It was illustrated during the Swiss National Exposition in Geneva in 1896 where Patek presented small 9- and 10-ligne Minute-Repeater movements (1 ligne = 2.255mm). As a comparison, the whole collection presented was standing between 6 and 21 lignes.

Hence we see how the will to offer smaller watches is part of the very early origins of Patek.

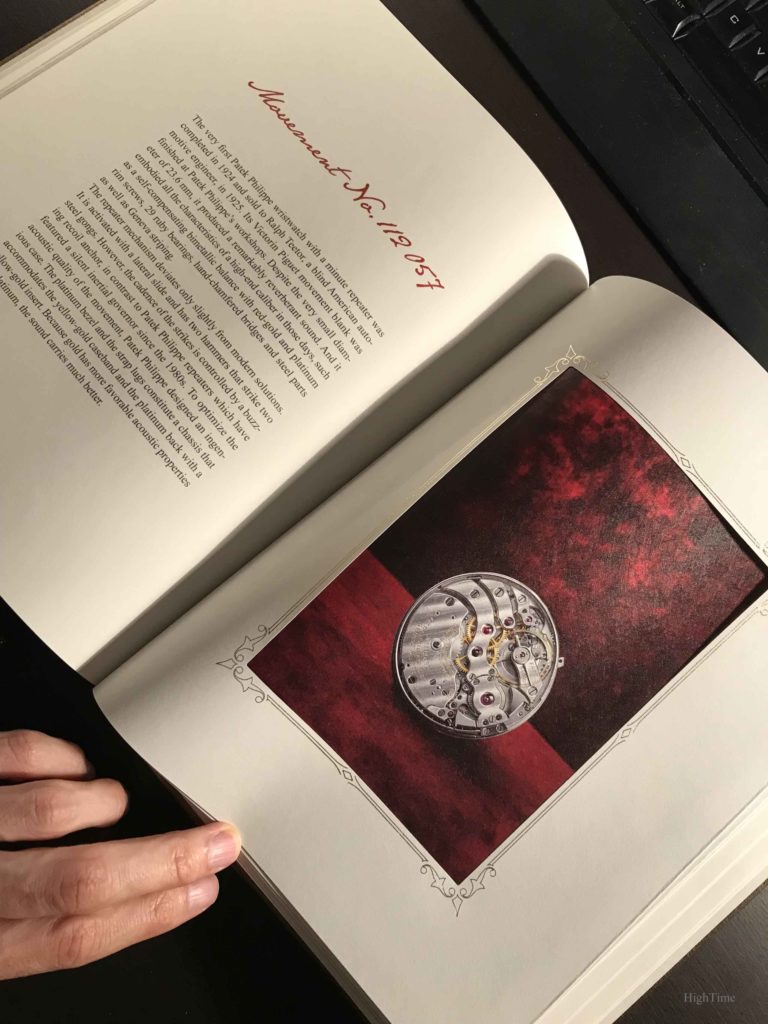

In 1906, the first Patek Minute-Repeater calibers for wristwatches, based on Victorin Piguet “ébauches” (an ébauche being a design of movement) were supplied to Tiffany in NYC.

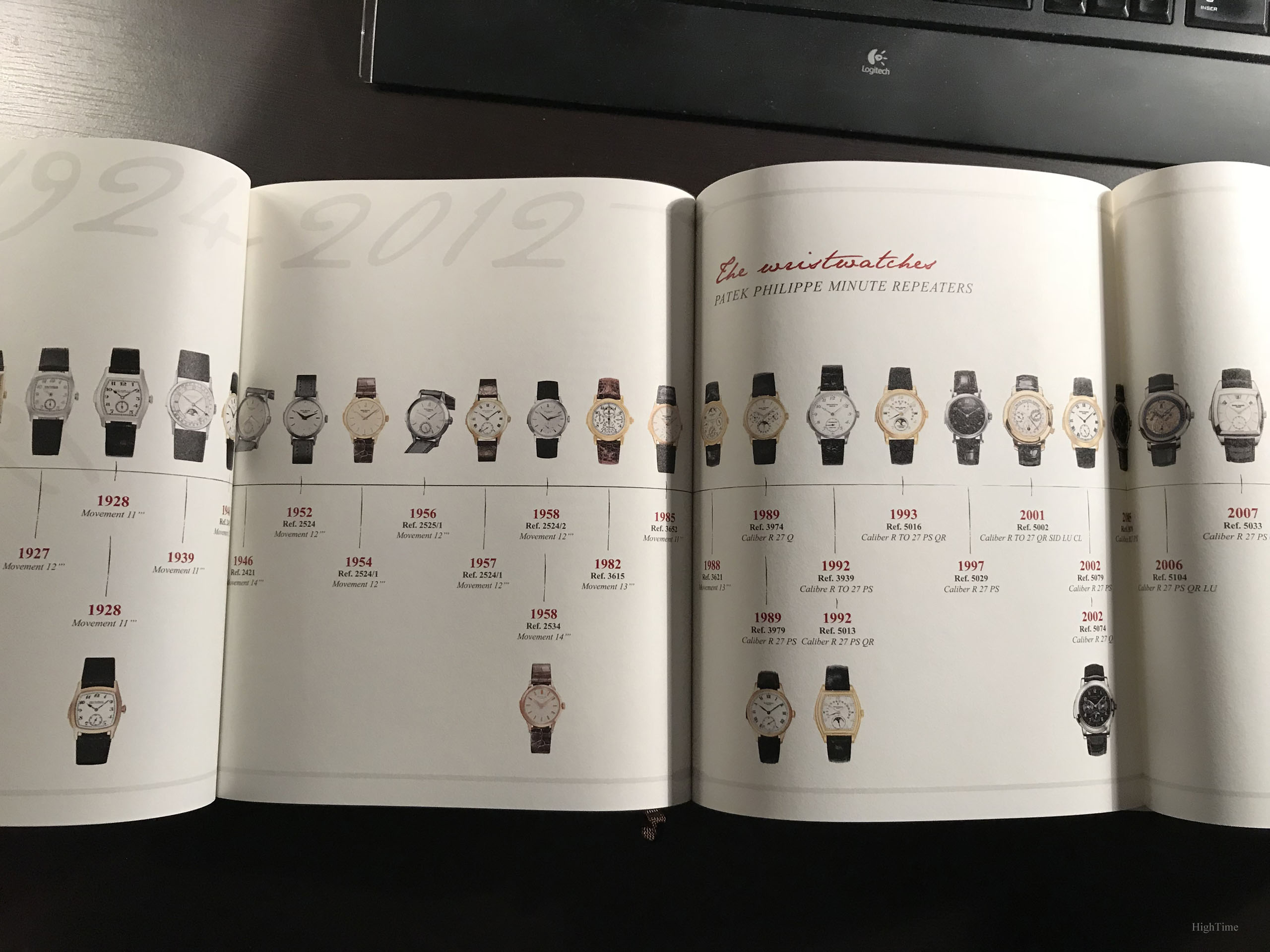

Then, the first Patek Philippe Minute-Repeater wristwatches appeared in 1920.

However, the regular production of Minute-Repeater wristwatches started in 1924. They produced 10- to 14-lignes calibers but favored the 12- ones as a good compromise between a smaller size (that could fit in 27mm cases) and the need for the right volume, i.e. high enough to get a good sounding. Indeed the cases were very small considering today’s standards but they stood that way in favor of a higher comfort on the wrist. Something we shouldn’t forget nowadays.

12 Art-Deco pieces (square-shaped cases) made of Gold and Platinum were produced at that time (4 are still visible at the Patek Philippe Museum).

After the WWII, around 30 of them were produced until the 1960’s (ref. 2419, 2421, 2524, 2525,2534), mainly in round-shaped cases.

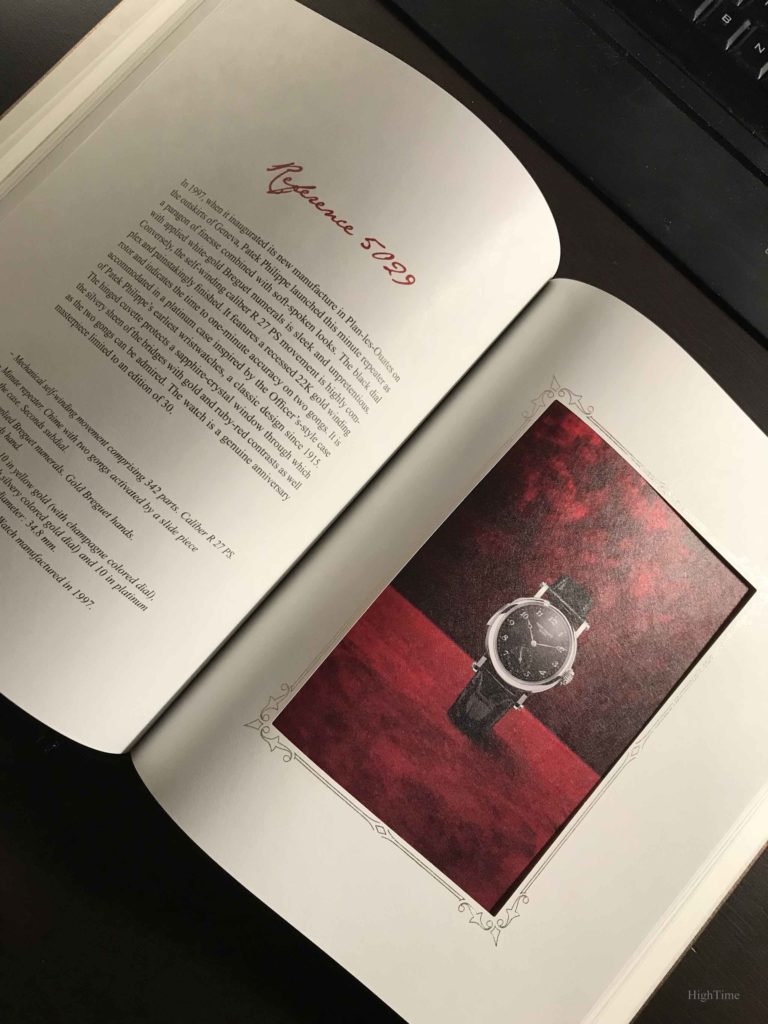

On the opposite of pocket watches, the wristwatches rarely offered another complication with the Minute-Repeater. The first one arrived in 1939 in Platinum with the Perpetual Calendar function (+ Moonphase indication).

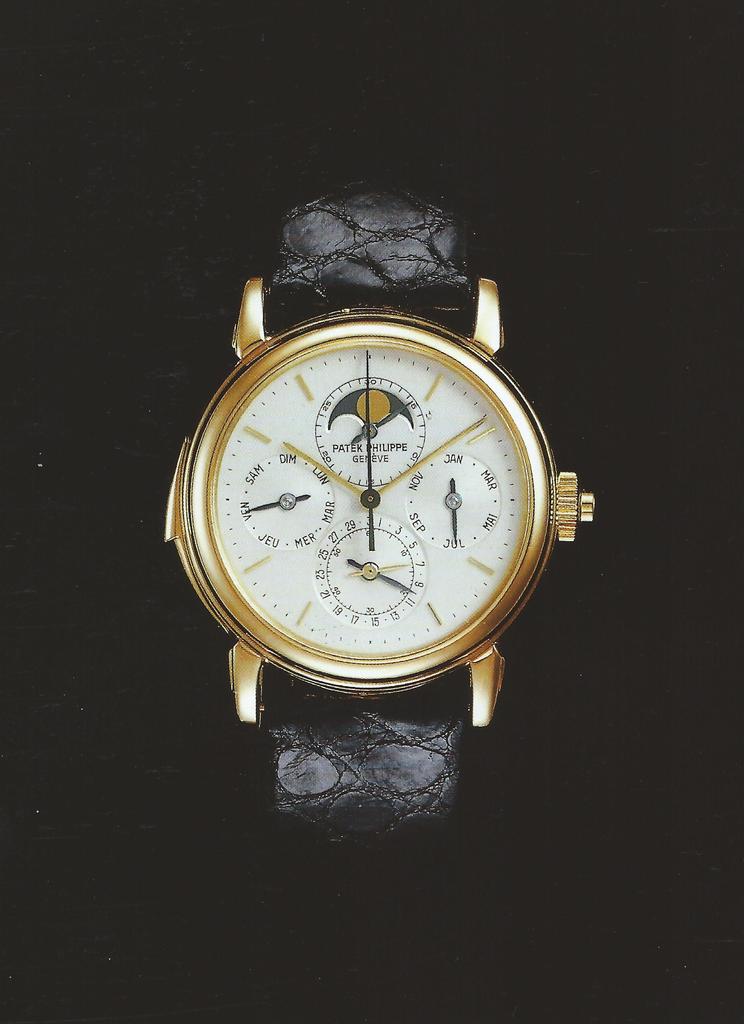

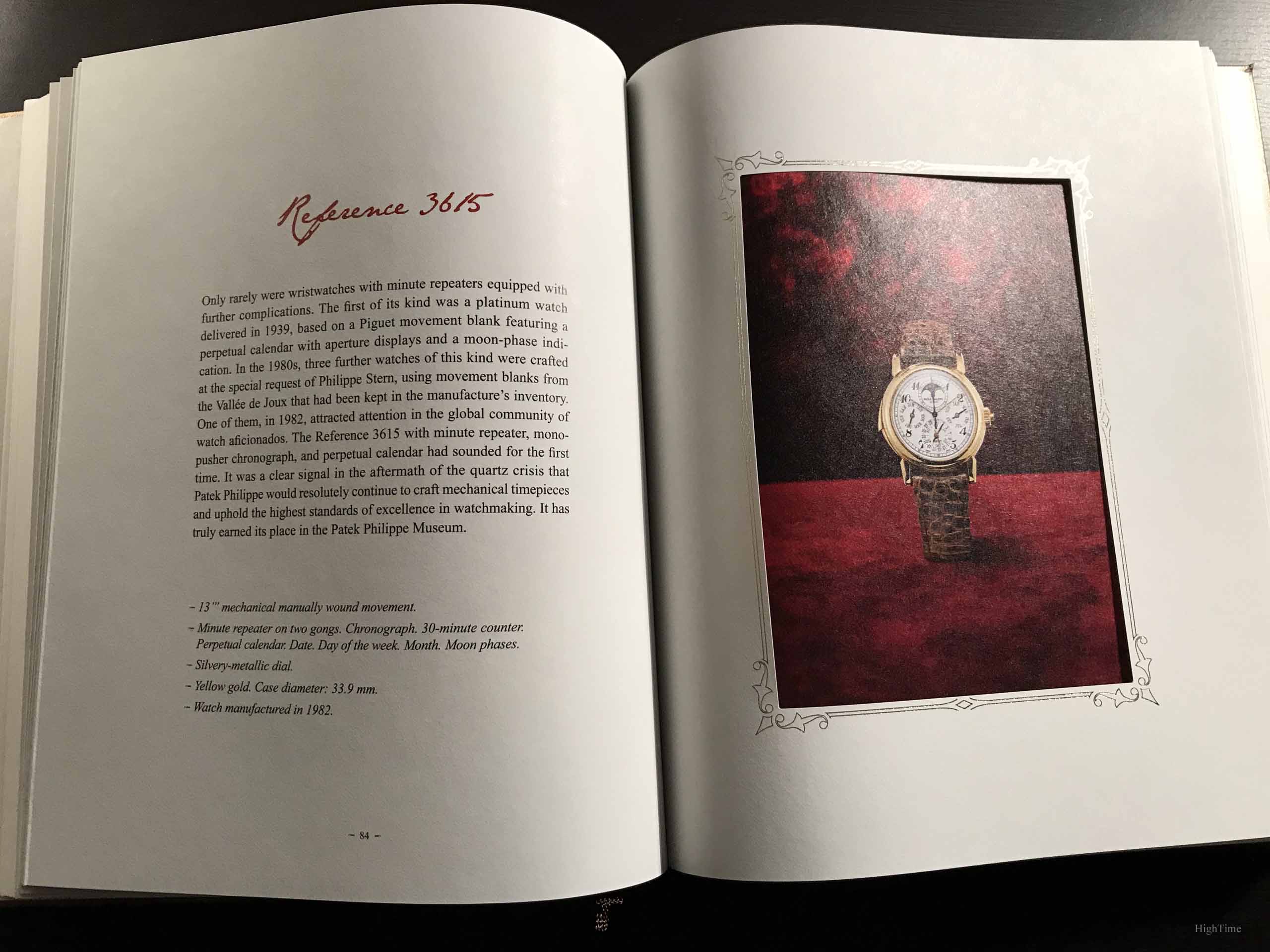

In the 1980’s, 2 Minute-Repeater + QP were made for Philippe Stern (Patek’s 1993-2009 President): one with the addition of the Moonphase and moon’s age (ref. 3621) and the other one with a Chronograph complication (ref. 3615 in 33.9mm!). Both used an old caliber base from the Vallée de Joux.

It’s important to notice that these 2 Minute-Repeater wristwatches crafted in the 1980’s were the first since around 20 years. It was indeed a time were no Minute-Repeaters were sold anymore (at least in the current official catalogue).

Hence, the decision of Philippe Stern to bring back this marvelous complication on the long run is a very important moment, historically speaking, for watch enthusiasts.

From then on, this was the beginning of a new era for Minute-Repeater pieces, marked by the decision to open a new chapter for Patek Philippe Minute-Repeaters, starting with the preparation of the 150th anniversary celebrations in 1989.

The Calibre 89 was then to be developed, with new technical and crafting approach of such feature and complications in general.

The Calibre 89

In the context of a will from Philippe Stern to bring the light again on what traditional watchmaking complication is about, in the most beautiful, rare and complex way, the brand has begun its journey towards the creation of the most complicated pocket watch for a long while.

Of course this would also have upsides in terms of image but the significant budgets involved since the launch of the new Lemania-based movement (3970 launched in 1986 with the new 27-70 caliber for instance) or the 240 caliber (patent from 1977) could have also been dedicated to less expensive models with still a strong marketing impact.

The endeavor of creating the Calibre 89, in my opinion, takes its source in a much nobler will from watchmaking lovers and Philippe Stern in particular. It’s I think the task of the most revered brands to take the lead in such fields. Patek Philippe picked up the torch.

If we observe this moment from another point of view, it was quite a courageous decision to decide to invest a significant part of the company’s resources for such a mechanical and “antique” device during the period of the huge success of the new quartz innovation (also called “quartz crisis” for mechanical brands). With all the going concern issues it implied for the company.

However, at that time, there were 2 pocket watches in that field:

- The Leroy 01 (Grand Prize at the Universal Exposition of 1900 in Paris) with 26 complications (including a few that aren’t horological-related like thermometer, hygrometer, barometer and compass);

- The famous Henry Graves made by Patek Philippe and delivered in 1933, with 24 complications.

Of course, the complexity depends on the type of complication (a Second-hand feature isn’t a Perpetual Calendar) and how it’s been implemented in the watch. The size of the caliber is also an important criterion to take into account (making smaller is much more complex, in size but also in reliability). As a side note, when we consider today’s 5175/6300 Grandmaster Chime, we can realize a little better what this achievement (size for complications) really represents.

The teams could handle the Henry Grave pocket watch as well as other very old pieces to document their complications and prepare the new blueprints and technical choices.

In the end (1986), the Calibre 89 was conceived with its 33 horological complications, including the Minute-repeater as well as the Grande and Petite Sonneries. The 33 complications weren’t a target in itself. It was more, as long as they added the different chosen functions, whether they could add additional ones or not.

This must have been such a thrill for the watchmakers involved in that project under the lead of Jean-Pierre Musy, to be given this opportunity. At that time there weren’t computer software for the design like brands use today (rather than using blueprints and small models). Moreover, the techniques used were all traditional, while each part had to be adjusted one after another until the final result is reached. It represented a long and painstaking “trial and error” process. Mr Musy said that, in that context, it wasn’t possible to implement the Westminster chime because of lack of room. However, this complication was added later in the Star Caliber 2000.

In the same period, Philippe Stern provided a few blank movements (from the Vallée de Joux) with a Minute-Repeater in order that a selected team learns, hence preserves, traditional forms of craftsmanship that weren’t performed as often back then.

The unique pieces 3615 and 3621, visible at the Patek Museum, were produced in 1982 and 1988.

You can see here below a third model, a very rare (possibly unique) “Ref. 96”-based Minute-Repeater, enamel dial, delivered in 1985: the 3652J reference (in 31mm). This watch was auctionned at Philips November, 9th 2019 for 572 000 CHF.

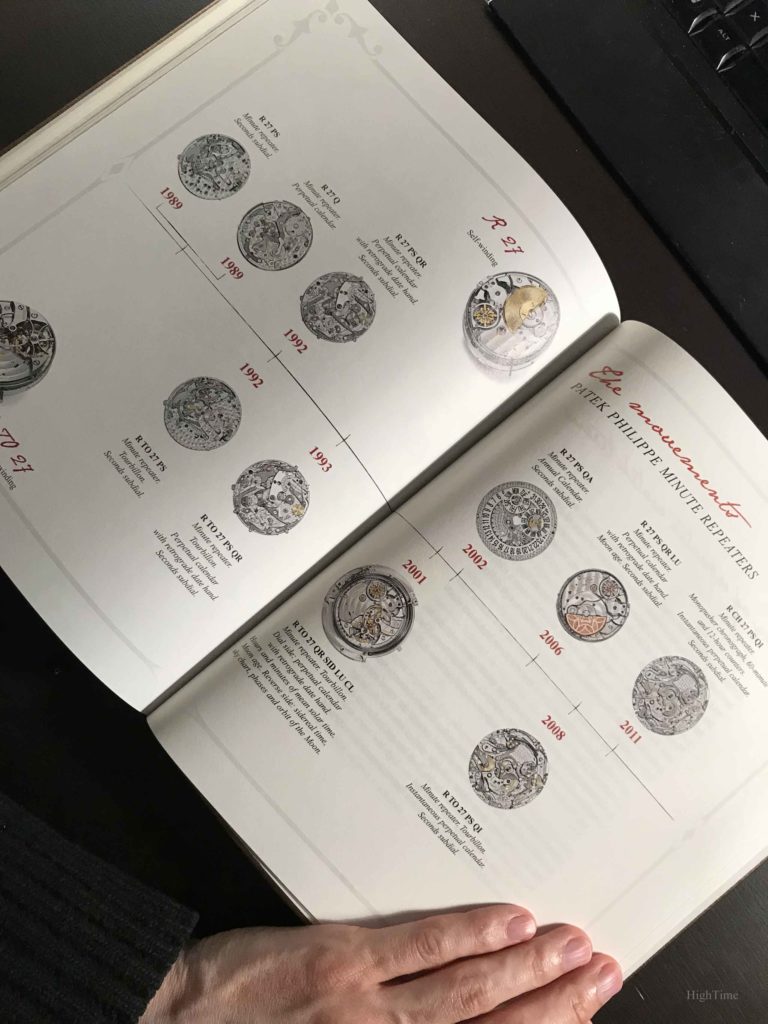

As a consequence, for the same 150th celebrations, Patek used the know-how they learned from the Calibre 89 to develop within 4 years a Minute-Repeater mechanism for 2 wristwatches:

- The Ref. 3979 with an ultra-thin self-winding Minute-Repeater caliber;

- The Ref. 3974 with a self-winding Minute-Repeater and Perpetual Calendar caliber.

This sums-up a chapter of determination, maybe even “faith”, to build a landmark in Patek’s history, and certainly for Watchmaking.

Technical evolutions

In spite of the traditional origins of Minute-Repeater designs, the brand was in a position to consider interesting improvements, yet still traditional.

A 1st key feature was to re-think the recoil anchor display that was usually used at that time, because of the background noise it creates. This part regulated the striking speed but wasn’t very reliable either, nor steady.

To try making up for these drawbacks, a friction governor system was developed in the late 19th century but leading to a higher wear and requiring a thicker movement.

Hence, for the Calibre 89, Philippe Stern gave his approval to deviate from the usual tradition to create a new friction-governor-based display. This work led to creating an inertial swivel arm system that naturally remained balanced at a certain speed while reducing significantly the aforementioned inconveniences. It is visible on the left side of the picture below: it’s the little “helix” we can observe spinning while the MR is activated.

A 2nd key feature concerned the addition of a self-winding display. The 240 caliber was an excellent base (free space left in the middle by the offset rotor, thinness) in order to add further complications in the future.

A 3rd major area concerned the gongs, a task that required some hard work: indeed, since the 1960’s, the gongs production had disappeared, with the suppliers, know-how etc…

An old watchmaker from the area, Henri-Daniel Piguet, worked closely with Patek to produce them again. The length and diameters are the 2 parameters the brand works on while setting a watch right (aside of the movement, case material and shape). The brand undertook meanwhile to create 1:1 scale blueprints in order to be able to reproduce them on the long run.

In parallel, the work was performed together with a Lausanne Institute in order to reach the best gong conception (acoustic behaviors etc…). Many secrets about crafting techniques (type of water used to cool the gong’s steel and other producing “tricks”) have then been researched and reproduced to craft again this essential element of 0.48 to 0.60mm in diameter.

The recording process of each Minute-Repeater has been implemented during that period and aims at understanding as many sound-rendering criterions as possible in order to master them better and better over time.

A specialist was hired in order to build up a diagram setting process. It should lead to create a complete Patek Minute-Repeaters database and help understanding possible issues and how to deal with sound in general.

About sound tuning

Aside of the strictly sounding matter, the watches should respect one of Patek’s guidelines: remaining thin and comfortable to wear. This is something that can be assessed from the past references and is harder to perform than in larger watches.

Considering new materials, Mr Musy states that it’s very difficult to reproduce or improve the acoustic qualities they have today and especially how they are able to apply the tuning process.

Small steps are sometimes better than a big change.

Therefore, the general guideline leads to designing a formalization process that will help keeping a higher and consistent crafting quality.

Hence, since 1989, Patek Philippe has implemented a whole strategy in order to improve their Minute-Repeaters’ sounding on the long run, until now and for the future.

Concretely, the teams are using a wide array of terms dedicated to defining very specific aspects of the sound, whether we talk about frequencies, clear and distinct tones, pitch, resonance, harmony etc… This glossary allows each technician to talk precisely about what constitute the final sounding of a Minute-Repeater (on Patek’s website here Acoustics on Patek’s website).

At the end of the making process, the watch can be presented several times to pass the validation Patek claims.

A few sectors are determined:

- The speed: its length should remain under 18 seconds for 12h59 in order not to spend too much power;

- The rhythm and strength: the last strike must be as loud and keeping the same pace as the first one;

- The volume: not too high, nor too low, even if the latter is preferred as it brings warmth.

A same watch may see a change of gongs, case of course but also all the positioning and setting of its elements.

Last but not least, even the side slide’s tension is something that is taking part in the pleasure of activating a MR. This slide’s function is to give energy to the spring that will power the complication. Indeed its power is separated from the hours and other complications spring barrel.

In the end, acoustic behaviors and how to set them aren’t something totally understood. Indeed the how and why they sound as they do remains a mystery on some aspects. Two watches build the same way will sound differently. Hence, only the experience brings a little more knowledge each time.

Issues considered

There are a few issues that watchmakers have to cope with.

Because of a lower material density, Patek recommends choosing Gold over Platinum cases. The density of the latter being 30% higher, the noise reduction is quite significant.

Another very important factor to deal with: the room available in the case considering the number of additional complications. More precisely, as parts “absorb” the vibrations, the fewer elements, the better, regarding acoustic quality.

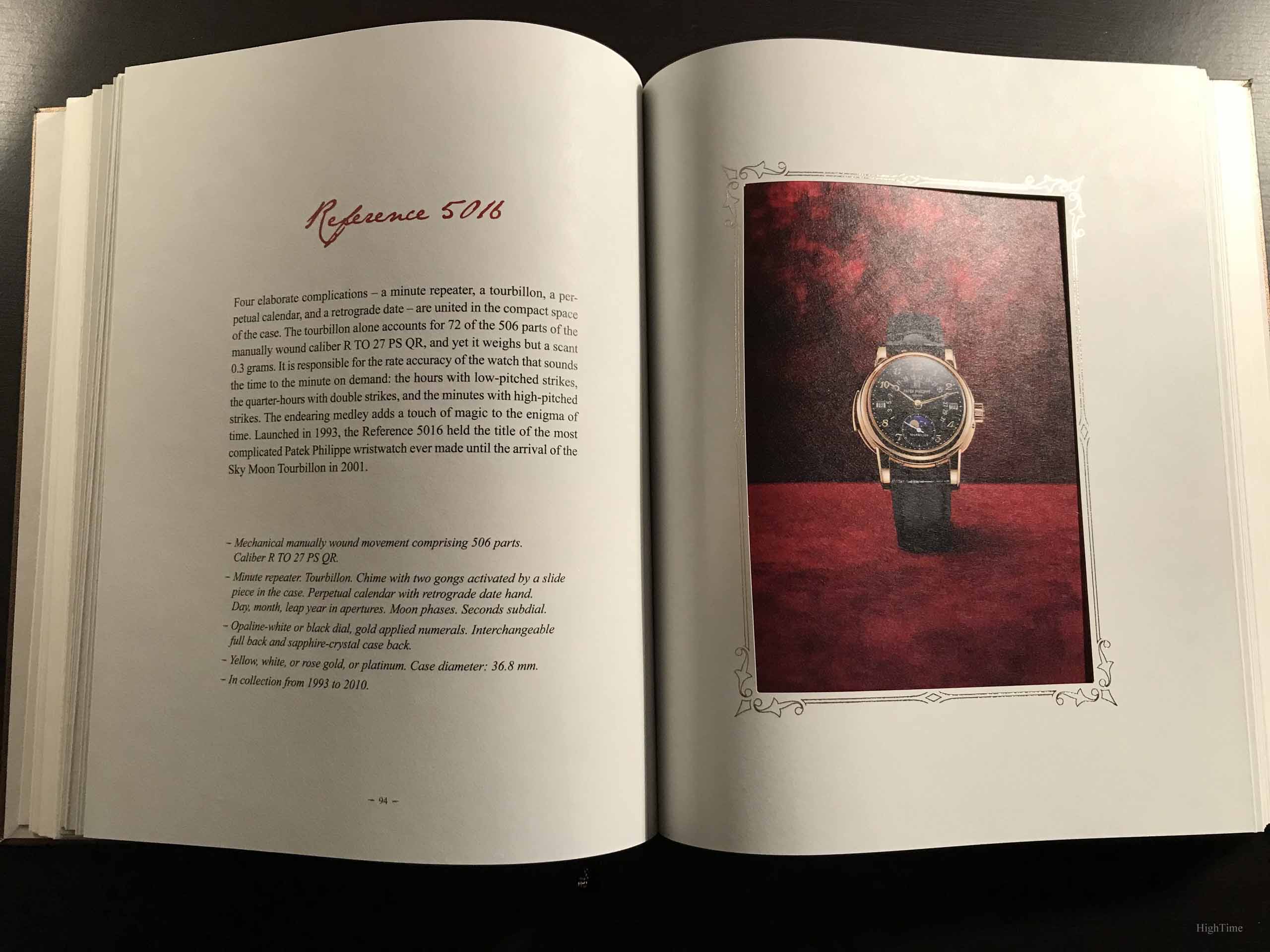

Considering a 331-part base caliber, the addition of the chronograph (160) or the Perpetual Calendar (210) is not neutral and shows once again the kind of challenges the watchmakers are facing for tuning such pieces.

As for the water-resistance matter, these pieces aren’t made for swimming-pools. Hence, the minimum is applied in order to limit air humidity and small drops. The case would get bigger otherwise, limiting the sound quality. Furthermore, the additional seal that the slide isn’t equipped with, would decrease the sound volume.

Patek Philippe certainly has the wider collection of Minute-Repeaters, whether they’re in the current catalogue or were proposed in the past. This, since quite a number of decades now.

Launching one single Minute-Repeater, sounding very loudly is something that can be done. But the volume isn’t the right benchmark. Indeed, mastering the charm of the music for the traditional nature of the exercise, and not for showing off or a one-time marketing purpose, is another story.

Conclusion and Thoughts

Well, this has been quite an Odyssey for the brand, to say the least. Now, for our own pleasure, a marvel from the past is still ringing at our horological door.

It looks now more obvious that there are stages to fulfill in order to reach the excellence regarding Minute-Repeaters. And it seems Patek might be a worthy knight in that matter.

However, for those who appreciate what the brand offers and more generally speaking about Patek’s Minute-Repeaters, their book is a great one to acquire (it isn’t a detailed catalogue of all the Minute-Repeaters the brand has produced either). It is illustrated with beautiful pictures and offers a clear presentation of this specific and romantic part of watchmaking, whether you wish to spend some time home, in a hotel… or else!

You can find more information on Patek Philippe’s website as well here:

About crafting Minute-Repeaters on Patek’s website

About “Sound” on Patek’s website

To see what’s in their library

Aside of the official website, here are 2 videos I would recommand:

A showcase from Hodinkee on their Youtube channel

A discussion between Revolution Watch on their Youtube channel and Thierry Stern

And I’m sure there are more interesting material dealing with this complication out there too.

Thank you for reading!