The Patek Philippe 30-255 caliber – The manual wind beauty is waking-up

Hi everyone,

In 2021, Patek has released a brand new thin manually-wound movement, the Patek Philippe 30-255 caliber. It was presented for the first time in 2 new Calatrava references, the 6119G and 6119R.

Since the 2 last decades, Patek Philippe has released, one after another, new calibers to keep progressing in the search of better accuracy and improving complications’ functionality as well as convenience. Indeed, in line with the origins of 3 or 4 centuries of watchmaking development aiming at miniaturizing clocks and improving working performance, watchmaking isn’t about standing still. It would have been easy to provide the same features forever, not mentionning the Quartz crisis, and we can’t deny what this brand has achieved over the last 90 years. Since a major technical and philosophical landmark around the brand’s 1989 celebrations (150th anniversary), Patek had engage in a daring endeavour (considering the 1980’s mechanical watches downturn) to develop even further its legacy. They owe their success to their own choices.

Hence, after several years, we witnessed from 2006 the launch of the 28-520 (automatic vertical-clutch flyback chronograph with column-wheel), the 29-535 (manual horizontal clutch with column-wheel chronograph), the exquisite 31-260 (automatic minirotor), the improved 26-330 (automatic 315/330 and 324’s successor) and now the manual-wind movement, the 30-255.

Movements aren’t just a question of functions. This is even the least important as far as the traditional watchmaking science is concerned. It’s more about how it’s done, how it’s being improved. Hence, we are talking about time-keeping, reliability, size, simplification, convenience for everyday’s life, etc… When finishing comes into play, we enter rarity fields.

PS: please note that I had to add a few official pictures because it was hard to take good pictures showing the caliber’s quality as deserved.

A legacy to introduce the new caliber

The 30-255 caliber is the successor of a longstanding manual thin caliber lineage. Indeed, Patek isn’t about the last 20 years only. I’ll just mention a few well-known movements to give an (non-exhaustive) idea. Since the 1920’s, there were a wide array of simple movements, especially through different sizes, labelled in number of ligne (French for line).

Nota: a ligne is an old movement diameter reference used in watchmaking. 1 ligne (written 1”’) = 2.256mm. For instance, the 12”’120 caliber is a 12-ligne movement.

Nota 2: from around 1960, they switched from ligne to millimetre. Hence why the 27-400 is 27mm, hence not written with the ”’ (yeah I know…).

While there are smaller, below 9-ligne movements and over 13-ligne movements, most of them were around the normal 10-ligne point (23mm). Hence, I will only name a few famous 9- to 12-ligne references.

- From 1930: “ultra-thin” 9-ligne 175 and 177 (heavily modified F. Piguet 21 base). More importantly, it was less than 2mm thick. The very small dimensions made very thin and elegant Calatrava models possible (the 177 was used in the 3520 reference for instance, 2nd picture below).

This point is very important for 2 reasons. First, because watchmaking was about downsizing, to the minimum for obvious reasons as room was limited, less weight means more comfort, etc… But it’s also what allowed refined and dressy looking models, which is still today valued as a standard for elegance despite sizes increase. Even though normal-sized Calatravas were elegant (like the 96, 565 or 570 equipped with the 12”’120), the 3520 (32.5mm) from 1965 was another sub-category of the simple time-only.

Hence, when discussing about movements’ size nowadays, should it fill-up the whole back side, it’s important to weigh-in with what a small movement allows in terms of size, hence the consequences in terms of consumption, inertia, etc… Not mentioning that, nowadays, the style side surpasses the original miniaturization philosophy.

- 1939-1975: 10-ligne versions (10”’105, 10”’110, 10”’200, 23-300). Back then, they were considered to be among the most revered manual-winding calibers. The 215 (further below) and 30-255 are the successors to this category;

You will notice that accross that long period of time, the spiral’s setting feature has changed with the removal of the raquette. This metallic curvy flexible part (on the balance bridge, picture above), which an end of the spiral is attached to, helps the watchmaker to set the spiral’s tension, hence the balance wheel’s pace.

The 1930’s innovations leading to find the Glucydur metal for balance wheels and Nivarox for spirals, were 2 major steps forward improving watches accuracy (lower magnetic and thermal sensitivity). Patek watchmakers who historically have put very hard work into watch development, have taken a few years to come with a reliable and performing solution. The brand finalized its groundbreaking Gyromax in 1951, with its famous small weights inside the balance’s rim. After a few years, with the addition of a free-sprung hairspring, the remaining regulating index disappeared (picture below).

- 1934-1953: the 12-ligne 12”’120 caliber used for around 20 years, developed “in-house” from the early 1930’s. It was aimed at replacing the LeCoultre-based caliber after the Stern family acquired the brand (1932). At a few early exceptions, the 12”’120 is the caliber giving life to the famous 96 reference (first Calatrava);

- 1946-1970: 12-ligne 27-CS caliber;

- 1950-1961-1983: 12-ligne 12”’400;

- 1960-1983: 12-ligne 27-AM-400 (antimagnetic).

- Afterwards (starting1974), following the early ages of Patek’s manual-wind calibers, a new era opened with the 215 caliber. The 2.55m 215 is the successor of the 10-ligne versions mentioned above. The 5196 or 5116/5119 were the last men references to house this movement until they were discontinued lately. There still are 4 lady pieces equipped with the 215 in the catalogue as of today.

This movement was a little simplified in the aesthetical way compared for instance to the 27-AM-400 (2 bridges becoming 1, no more inward angle decorations), in the context of the 1970’s-1980’s downturn, but the execution, whether on the finishing techniques or on the functional levels, was excellent. You may notice that we have a visible decorated barel Rochet and Crown wheel which were hidden prior to the 215 (upper left side, picture above).

Its size was a last representative of the original 96 reference’s spirit as it was even included in the 30.5mm 3796 (1982-1999).

The 30-255 as the following step

And not only the following step but the successor. It’s difficult to really assess from pictures how important, hence well-crafted or technically advanced, calibers are. Especially while dealing with older ones. While today we have HD pictures flowing through the internet, it’s more difficult to get nice shots of good shape old calibers. As usual, the real experience is mandatory (as well as technical knowledge) to understand how they stand. You won’t see the truth from pictures only.

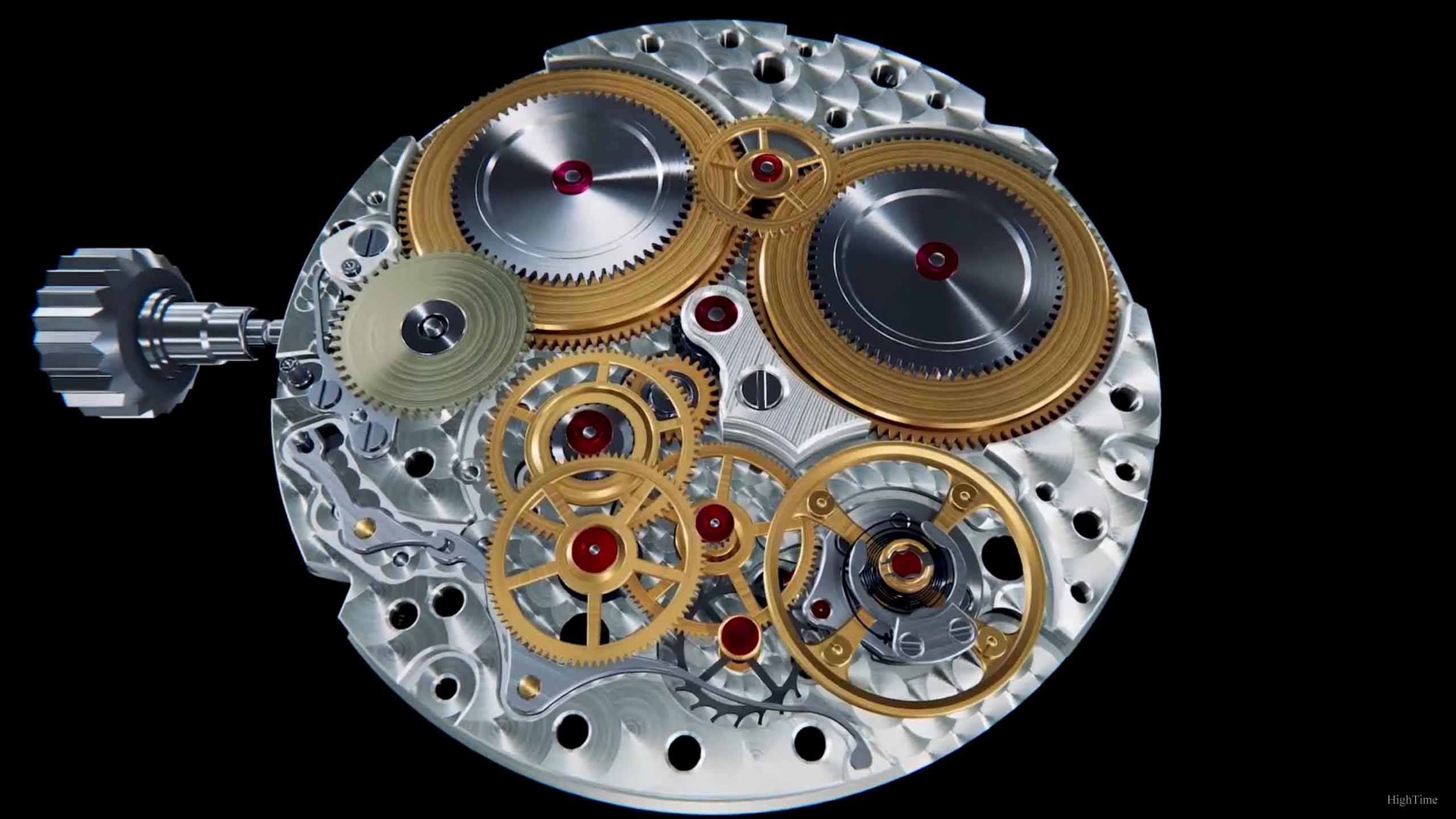

Dimensions observation

Starting with its dimensions, it is 30.4mm wide while it remains (vs the 215) at 2.55mm in thickness (hence the “30-255” name, following Patek’s usual nomenclature for calibers). Watch diameters have increased these last years, especially since size is a relative matter, to be compared to the wearer’s wrist. What matters is the proportion, not the absolute size itself. Many have bigger wrists than in the 1940’s and the standard aesthetical trends have also played a role.

However, what the thickness of the caliber says is that Patek will keep on making thin watches, as they should considering very elegant and refined models (not mentioning its impact on comfort, wearability, etc…). What it also says is that Patek are limiting themselves to provide smaller diameter cases because of this 30.4mm restriction (21.9mm for the previous 215 caliber, which is a huge difference). At least for this manually wound caliber.

As a comparision, the 29-535 manual chronograph is 29.6mm in diameter, the 26-330 (ex-324) is 27mm and the 28-520 automatic chronograph is 30mm. Thus, all remain smaller.

About better time-keeping performance

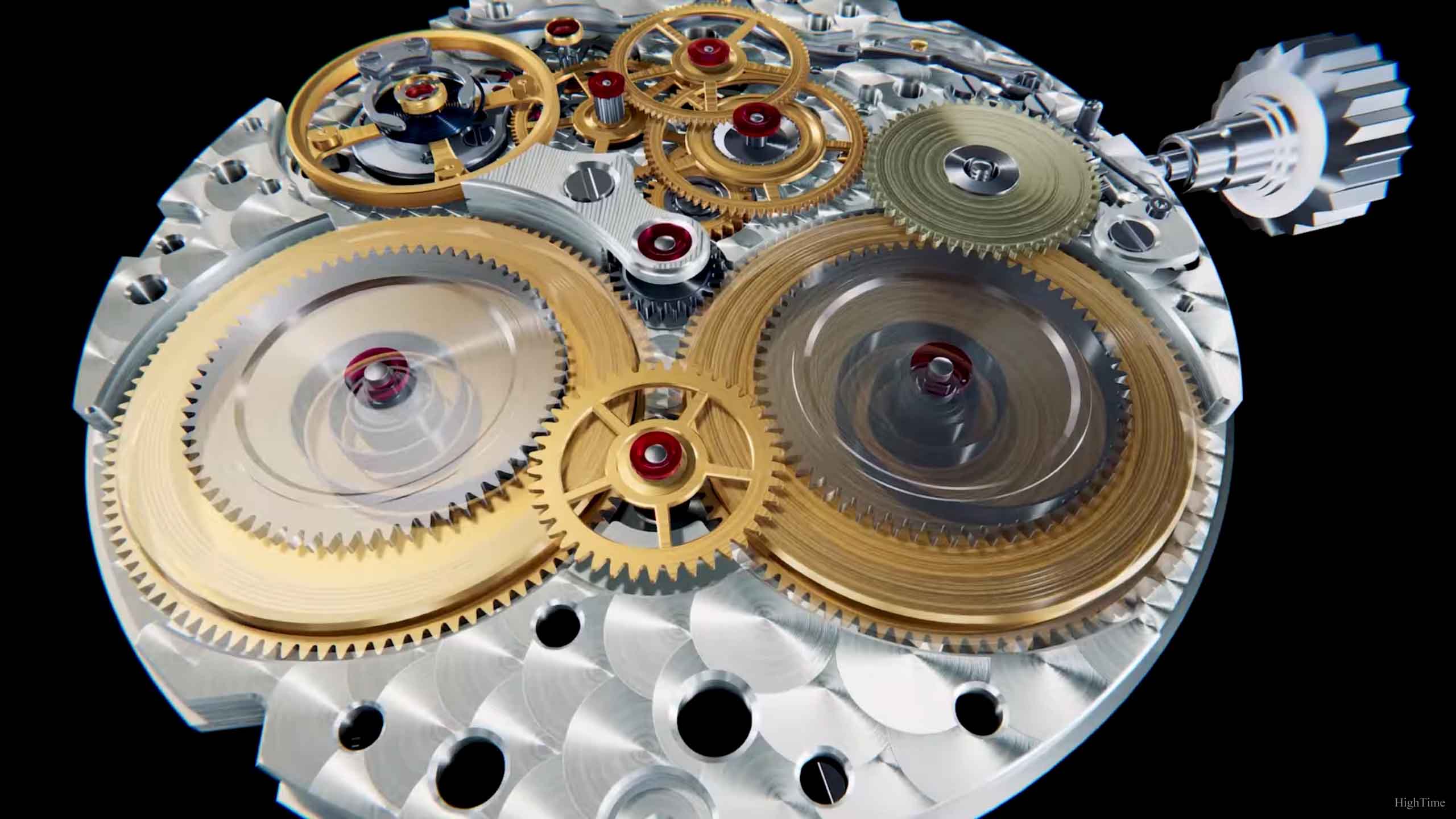

The main reason, their committed stance, is the introduction of a twin barrel system, assembled in parallel, that provides a 65h power reserve along with an excellent accuracy. Good time-keeping and long power reserve are in theory working in opposite directions. When the tension in the mainspring decreases, its ongoing force to drive the escapement logically weakens compared to friction forces and everyday shocks.

Patek has also used its experience within the 10 days 5100 “Manta Ray” and 8 days 5200 Gondolo movements which also had an in-line 2-barrel feature. They used thicker barrels to get even more power reserve (the movement’s height was nearly twice as thick as the 30-255’s, hence bigger spring for more PR).

This conceptual flaw makes it also difficult to set the movement for the beginning and for the end of the power reserve at the same time. As a fully-wound mainspring torque is higher than when it comes to the end, when it fuels the “kick” of the balance wheel, its angle will be more or less important. This impacts directly the beating frequency, hence time-keeping. By the way, some watchmakers still recommend in some cases to wind everyday a watch with a 50h+ power reserve.

To use an automotive world analogy, a combustion engine has a maximum Horse Power at a certain regime (usually the peak of torque as well). All things being equal, a good engine’s curve will approach that “peak” number before and after that specific regime, with a “flatter” inclination.

The significant difficulty for watchmakers is historically to compensate the phenomenon by different means like logically increasing the mainspring’s strength (at the cost of a much higher stress on the whole gear train and limited by the room required for a large single barrel), using a fusée-chaine feature (at the cost of complexity, occupying more volume, more expensive), etc… To help finding a more efficient way to improve this decrease in torque through the whole period, Patek has chosen to implement 2 barrels, side by side, together with modifying the transmission of the energy through a modified pinions and wheels architecture.

As a result, the torque supplied helps fueling the balance wheel with roughly twice the inertia (10 mg/cm²) of other 4Hz Patek movements. This is what helps providing a steadier beating pace over the whole power reserve, thus ensuring to have a very accurate manual wind Calatrava. Indeed, obtaining a higher power reserve to the detriment of accuracy would be nonsense.

Additionally, the fact both barrels are placed in parallel helps lowering the mainsprings’ height (less individual strength required). Meanwhile, on the contrary to previous calibers, the central pinion and intermediate wheel’s bulk was reduced by decreasing their size while keeping a robust design to sustain the increased torque (cf. picture below, the steel and brass small “monolithic” wheels in the center, between the barrels). This leads to keeping the movement’s thickness low.

As for the 215, the new caliber’s escapement beats at 28,800 vph (4Hz).

Besides, the 164 parts 30-255 caliber is now equipped with a feature that was missing in previous Patek movements: a stop-second feature. You can see at the bottom side of the 2nd picture above, the braking arm that stops the balance wheel when the crown is pulled (it’s visible in action in the small video linked at the bottom of this article).

How beautiful it is

Now, when dealing with aesthetics, this is especially the field where the 30-255 shows to be faithful to the high standards of Patek. When looking at high-end manually wound 2- or 3-handers from traditional established brands, we often face simplified calibers, whether in terms of bridge shapes or about finishing (especially minimum required level edge polishing). Even if the general design concept can’t always be revolutionised, some “new” in-house movements come closer to third party revamped versions. In that context, the previous 215 was already something above what many offered if going into details.

During the 1970’s-1980’s, times (and business) were rough for the mechanical watch industry. Quartz was thriving. It was more precise, more convenient for sportier activities, much less expensive, requiring less servicing, etc… More generally, it was modern, hence cool, it was watches’ future. Despite traditional brands’ going concern was at stake, Philippe Stern (Thierry Stern’s father) decided, as early as in the early 1980’s, to boost the development of complicated movements and re-introduce mechanical watchmaking as an art but also as an expression of men’s ability to miniaturize everyday mechanical little marvels. It was the start of the 1989 150th anniversary preparations, leading to the illustrious Calibre 89 and other Minute-Repeater wristwatches rebirth at times when CAO wasn’t a thing but rather blueprints and wooden models. Those “lost” complications during a period when Quartz was in the spotlight was an act of faith.

Much later, as times for mechanical watches brightened up, especially over the 3 last decades, we saw that Patek had decided to offer its vision of a new caliber generation. It isn’t a question of doing in-house for the sake of marketing only. It’s mainly that starting from a blank page allows to express all a brand’s philosophy and aquired know-how, without the limitations of a third-party movement supply (Lemania or F. Piguet for instance). The development of the upper strata of Grandes Complications at Patek is on an even higher level of delivery.

This is even more interesting noticing that the 215, 315 and other 240 minirotor calibers are still today excellent in their fields compared to their competitors, whether in terms of timekeeping and reliability but also, what I wish to emphasize, in terms of aesthetics. They aren’t copies from third party bases. Again, I’m not talking about Independents here, just large established brands.

Thus, as mentioned in the introduction, since 2006, we already witnessed the launch of the 28-520 (automatic chronograph), the 29-535 (manual chronograph), the 31-260 (automatic minirotor) and the improved 26-330 (automatic 315/330/324’s successor). I didn’t mention the more complex Grandes Complications. The exception would be Lange, even if they play in a sub-5000 production field, which is a major differentiating factor. Their 1990’s rebirth helped them to start on the right track straight away, with the talent of the right people. On the other hand, ongoing traditional brands didn’t take the risk Patek took.

Today, the 30-255 brings a lot to a very shy and quite old manually-wound caliber world. The new 30-255 brings back very elaborate shapes, in the continuation of the early 1930’s-1950’s models and that’s excellent news. The 30-255 is indeed gorgeous and it’s clear that the brand didn’t make a new caliber with just the “minimum required level of shine”. They thought that it shouldn’t be the poor relation of movements because it’s the simpler one, equipping less expensive references. It had to have its own beauty and finishing interest. I would say the only and sufficient reason is that it was meant to equip the Calatrava.

I find, personally, that this movement looks even better than the famous automatic 324/26-330 caliber. And it wouldn’t be an insult to say the bidges work are even more appealing than on a 240 minirotor’s, which is considered as one of the most charming in Patek’s catalogue. My take on this is that they wanted to make a pleasure equivalent of a manual-wind chronograph applied to the simple manual movement field, taking advantage of the lack of the automatic feature (rotor, wheels…).

The bridge shapes are the main elements showing that the manual wind movement is being put forward as a fine example of craftmanship. The curves are (much) more elaborate than on the 215 and the angles are more spectacular, especially while looking at the central bridge (here below).

This sharp central bridge reminds me of the one we find only in the very high-end 29-535 caliber in its Split-second version (5204), which is quite a statement:

The semi-circle cut in the main bridge is also a nice way to surround the second wheel. Those lines also follow the 2 barrels roundness in order to include them coherently in the movement, while playfully contrasting with the Côtes de Genêve.

The overall picture including the jewels, their gold chatons and the black polished screws is outstanding as well as refined, while never falling into visually overloading the topside.

This movement was a surprise, I don’t think many (me included) expected Patek would set such high level of requirements for this project. In a world where the balance between marketing and pure dedication to craftmanship is often mediocre, I’m glad they aimed toward such outcome.

Conclusion and Thoughts

When dealing with manual wind movements, people often consider they are too “simple”, hence less deserving interest than more complicated ones. My original motivation for this article came from the fact I got more and more excited as I could handle a 30-255 Patek Philippe a few times. Was I missing something? As months passed, with different experiences, especially when I had a look at the state of these calibers around the established brands world, I thought this was a pity and I couldn’t understand the missed opportunity not to refresh that field. Were brands lacking of courage or interest? Sometimes we get picky when it comes to Patek but we don’t really realize what they are bringing.

We often aim at or feel more attracted by complicated watches and this is totally understandable. Nevertheless, we also notice collectors considering going back to a simpler model, for its refinement, discretion and beauty. But the fact a 2 or 3 hander didn’t rhyme with a spectacular movement as much as a 240, 26-330 or 31-260 caliber was a rock in the shoe for people caring about a movement’s decorative prowess. By the way, the 5227‘s thin officer’s caseback and 5226G’s case design and decoration are examples of underrated areas to focus on, thus making these watches much more interesting than people think.

Going through a movement in details in real, though a watchmaker would have much more to say, is a very instructive and enjoyable exercize in order to learn what is invisible but brings more. Considering the micro scale from which a movement is judged, whether we talk about efficiency or reliability, it’s important to have an idea of what’s at stake, what Patek has put in terms of efforts and the means required to come to that end. This is certainly a reason why many don’t do it while still providing an honorable minimum (usually). It’s overall a long-acquired experience deployment. Visual excellence isn’t always in par with technical prowess. That’s why I think it’s important to deepen our understanding of movements.

I already had enjoyed discovering and going in-depth the new and sublime 31-260 minirotor caliber. This movement was already a landmark on its own inside the 5236P and 5326G but it wasn’t over. The 30-255 caliber is beautiful, efficient and time will tell if it’s reliable but knowing Patek’s track record, I wouldn’t doubt it. More than these aspects, in coherence with what the brand has offered over nearly the 2 last centuries, with hardly no pause, you get in this movement a portion of Patek’s craftmanship heritage. And it’s not just fame. This movement isn’t an entry model material. It’s today’s completion of a long lineage of evolutions, during rough and good times. Therefore, getting a 30-255 based reference, like the 6119G or R currently, could be an aim on its own for any collection.

You can find here Patek’s video on Youtube:

Patek’s 30-255 caliber 3D video

As usual, you can find more about movements on Patek’s website here:

Thank you for reading!